23 Perspectives on Free Will w/ Top Physicists & Philosophers

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Michael Levin

- David Wolpert

- Donald Hoffman

- Stuart Hameroff

- Claudia Passos

- Wolfgang Smith

- Bernardo Kastrup

- Matt O'Dowd

- Anand Vaidya

- Chris Langan & Bernardo Kastrup

- Scott Aaronson

- Nicolas Gisin

- Brian Keating

- Lee Cronin

- Joscha Bach

- Karl Friston

- Noam Chomsky

- Stephen Wolfram

- Jonathan Blow

- Thomas Campbell

- John Vervaeke

- James Robert Brown

- Anil Seth

- Source

Introduction

The question of whether humans have free will has been debated by philosophers and scientists for centuries. Do we have the ability to make choices that are not entirely determined by prior events, or is our sense of agency and volition just an illusion?

This post explores perspectives on free will from some of today's leading thinkers across a range of fields including physics, neuroscience, mathematics, computer science, and philosophy. While there is no consensus, their views shed light on the complexity of the topic and the different ways free will can be understood.

Some, like physicists David Wolpert and Donald Hoffman, argue that free will as traditionally conceived is incompatible with deterministic physical laws. Others, like philosopher and cognitive scientist John Vervaeke, see free will in a compatibilist sense - not as uncaused causes but as our cognitive states being the most relevant causes of our behavior.

Many connect free will to broader questions about the nature of reality, consciousness, and the self. Neuroscientist Anil Seth views the experience of free will as a kind of useful perceptual hallucination, while entrepreneur Stephen Wolfram suggests notions of free will may relate to the computational irreducibility and unpredictability of complex systems.

There are no easy answers, but examining free will through the lens of modern science and philosophy can enrich our understanding of human agency, morality, and the mind. The diversity of views presented here reflects the enduring mystery and significance of the question.

Michael Levin

- Questioning whether the world's inputs to us have anything to do with our actions requires representative capacity and memory.

- The dynamics that break up an undifferentiated ocean of potential cells into one or more embryos can go different ways. Out of this ocean of potentiality, cells will have specific goals.

"I think it's very plausible to say that any organism that's self-constructs, under energy constraints, is going to believe in free will...it's the realistic limitations on primitive agents that—the time and energy that they cannot be Laplacian demons—and so they have to tell stories...about other things doing things...and in fact themselves doing things because that allows you to make very parsimonious...algorithms for your own behavior."

Levin argues that the traditional free will debate, which frames it as either determinism or randomness, is a false dichotomy. He believes that what we consider "free will" is not something that can be applied to a single, narrow event or moment in time. Rather, free will is exercised over longer periods of time through the development of our character and habits.

As Levin explains: "The deal is that in any one slice, whatever is going on is determined by things you have no control over. I mean, what is the next thought you're going to have? You don't control your next thought. Your next thought is whatever pops up. At the moment, that's what pops up. However, over long periods of time, which you have control over, is the statistical spectrum of the kinds of thoughts you're likely to have."

In other words, while we don't have control over individual thoughts or actions in the moment, we can shape our overall character and tendencies through consistent effort and practice over time. Levin sees free will as a "symphony of choices over time" rather than a single, isolated decision.

Levin argues that this view of free will as a long-term, emergent property, rather than a moment-to-moment phenomenon, is more in line with our actual lived experience and intuitions about agency and responsibility.

youtube.com/watch?v=nWMSlcZbEMw

commentary.org/articles/michael-levin/thinking-about-the-self

thoughtforms.life/a-short-dialog-between-an-applicant-who-doesnt-believe-in-free-will-and-a-hiring-manager-at-a-software-company

David Wolpert

- Objectivists say probabilities point to some real random generator in the world. Subjectivists say probabilities are just degrees of belief.

- The common notion of free will is some non-physical, ill-defined means by which cognition can abrogate deterministic laws of science. He sees no evidence for this and it's irredeemably far from what is meant philosophically by free will.

- Redefining free will in a provable way to claim you've proved it is a rhetorical fallacy (Motte and Bailey) - the reasons it was originally controversial get defined out.

- Even if an observer's choices seem "free", they are still determined by the observer's characteristics and properties. To be is to have properties.

Wolpert has argued that the concept of free will is fundamentally incompatible with the laws of physics and mathematics. He has claimed that there is a "non-quantum mechanical uncertainty principle" that places fundamental limits on what can be predicted or controlled, even in principle.Wolpert has stated that "every model must contain assumptions and that there's no way to prove a given strategy will outperform all others in all possible [situations]." This suggests that true free will, where an individual can make completely unconstrained choices, is not possible given the constraints imposed by the physical world and mathematical principles.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_will

philpapers.org/browse/pancomputationalism

complexity.simplecast.com/episodes/45/transcript

Donald Hoffman

- Under physicalism, free will is a useful fiction. In his conscious agent theory, probabilities could be interpreted as free will choices.

Hoffman believes that our perceptions do not accurately reflect objective reality. He argues that evolution has shaped our perceptions to maximize fitness, not to represent the true nature of reality. As he states, "According to evolution by natural selection, an organism that sees reality as it is will never be more fit than an organism of equal complexity that sees none of reality"

Hoffman proposes a "conscious agent" theory, where reality is fundamentally composed of "conscious agents" rather than physical objects. As he explains, "I believe that consciousness and its contents are all that exists. Spacetime, matter and fields never were the fundamental denizens of the universe but have always been, from their beginning, among the humbler contents of consciousness, dependent on it for their very being"

In essence, Hoffman argues that the world presented to us by our senses is an "evolutionary illusion" and that the true nature of reality is fundamentally composed of consciousness, not physical objects

quantamagazine.org/the-evolutionary-argument-against-reality-20160421

sites.socsci.uci.edu/~ddhoff/Objects_of_Consciousness.pdf

link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-03633-1_11

Stuart Hameroff

- Free will may be possible due to backward time effects in the brain, based on Libet's experiments showing a half-second delay between brain stimulation and conscious experience.

-

Orch OR identifies discrete conscious moments with quantum computations in microtubules. Each Orch OR quantum computation terminates in a moment of conscious experience, and selects a particular set of tubulin states which then trigger (or do not trigger) axonal firings, the latter exerting causal behavior. This can in principle account for conscious causal agency and free will.

-

Orch OR can cause temporal non-locality, sending quantum information backward in classical time, enabling conscious control of behavior. Hameroff presents three lines of evidence for brain backward time effects, which can avoid the problem of consciousness appearing to come too late to influence behavior.

-

Penrose OR (and Orch OR) invokes non-computable influences from information embedded in spacetime geometry, potentially avoiding algorithmic determinism and allowing for free will.

In summary, Hameroff argues that his Orch OR theory can account for real-time conscious causal agency and free will, avoiding the need to view consciousness as an epiphenomenal illusion.

youtube.com/watch?v=ztGNznlowic

singularityweblog.com/stuart-hameroff-quantum-consciousness

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3470100

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orchestrated_objective_reduction

Claudia Passos

- Behavioral markers like flexible responses to avoid pain could be indicators of consciousness, as opposed to just automatic reflex responses.

Wolfgang Smith

- Free will pertains to our present state of partial knowledge. Once we attain enlightenment, there is no more free will because there is no more will as we know it. Love in its highest sense is inseparable from God.

Smith argues that the doctrine of free will asserts that in some cases, the "Ego alone is the determining cause", while the doctrine of determinism claims that in every case, the outcome is determined. He critiques various philosophical models that try to reconcile free will and determinism, such as those proposed by Daniel Dennett and Robert Kane.

Smith contends that the key issue is "locating the master switch and the mechanism of amplification" that would allow indeterminism and free will to exist in the brain. He suggests that if libertarian theories of free will are to succeed, "something similar [to a randomizing mechanism] must go on in the brains of humans."

Overall, Smith seems skeptical of the ability of modern science and philosophy to satisfactorily resolve the free will problem, stating that the "basic failure is his location of indeterminism making chance the direct cause of action." His views appear to challenge the prevailing scientific worldview on this issue.

informationphilosopher.com/freedom/mechanisms.html

philarchive.org/archive/BENTEO-44

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolfgang_Smith

philos-sophia.org/gnosticism-today

http://www.worldwisdom.com/public/viewpdf/default.aspx?article-title=Science_and_Myth--The_Hidden_Connection_by_Wolfgang_Smith.pdf

Bernardo Kastrup

- Nature is a force that generally controls us more than we think. We are an aspect of it, not separate from it. Our choices are instinctive and determined by what nature is.

Free will is not the ability to make choices unconstrained by external factors, but rather the capacity to make choices determined by one's own desires, preferences, and intrinsic nature. As Kastrup states, "What most people mean by 'free will' is that my choices are determined, but they are determined by me ... My choice is only free if it is determined solely by what I perceive as my preferences, my tastes, my desires, my dispositions, my plans, my wishes, my fears."

Kastrup argues that our choices are ultimately determined by what we are as individuals, and we cannot be other than what we are. As he explains, "What you do will always be determined by what you are. Our choices are consequence of what we are, and we cannot *not* be what we are. So, in that sense, there is no room to play here. Our choices are a function of what we are, and we are what we are."

In Kastrup's view, free will does not mean making arbitrary or random choices, but rather making intentional choices based on our own subjective experiences and inner nature. As he states, "An intentional choice must thus be determined by something; by some set of determining factors. The essential question here, which I think most people overlook, is: What factors? The core of our intuition about freewill is that the determining factors must be internal to us as subjective agents."

sloww.co/free-will-bernardo-kastrup

bernardokastrup.com/2014/05/freewill-explained.html

essentiafoundation.org/the-red-herring-of-free-will-in-objective-idealism/reading

conscienceandconsciousness.com/2020/07/08/response-to-bernardo-kastrup

youtube.com/watch?v=zoOi79nQywE

Matt O'Dowd

- Free will is real in a meaningful sense, because choice is a fundamental component in the dynamical system of the mind, independent of the physical substrate. The universe conspires to always be self-consistent for all observers.

Anand Vaidya

- Speaking a language is an agential activity involving some degree of free will in constructing meaningful sentences. If we don't have free will, then we're not really communicating, just parroting sounds.

- What gives something moral standing is computational intelligence that is goal-directed and tied to preferential states, not necessarily free will.

Chris Langan & Bernardo Kastrup

- Langan: Free will happens because things are determined metacausally and metaformally through coupling/factorization, not linear causation. It gets out of the pseudo-causal dichotomy between determinacy and indeterminacy.

- Kastrup: At the level of universal mind/consciousness, the question of free will disappears because choices are still determined but they are determined by what the mind of nature is. Need and choice are one and the same.

Scott Aaronson

- If a computer could perfectly predict his actions before he does them, it would shake his sense of free will. But whether such a prediction machine can exist is currently an open empirical question, not settled by known laws of physics.

- In the Newcomb's Paradox thought experiment, one-boxing is the right choice if you consider that the predictor has effectively brought into being a second instantiation of you. You have to reason as if you're the simulation.

Nicolas Gisin

- Claiming science has proved free will is an illusion is taking physics too literally as a religion. It's an overstatement.

- For him, free will comes logically first before any arguments about its existence. Arguing against free will requires using your own free will.

- Our decisions are extremely influenced by our environment but not fully determined by it. There is room for some free decisions.

Brian Keating

- Keating operates as if free will exists but is agnostic. Knowing for certain there is no free will wouldn't change his behaviors and interactions. But if proven God exists, that would have huge behavioral implications.

Lee Cronin

Cronin believes that free will is about being able to explore a "narrow trajectory" that allows you to make choices about what you build or create. He says "Free will is about being able to explore on this narrow trajectory, that allows you to build... You have a choice about what you build. Or that choice is you interacting with a future in the present."

Cronin rejects the idea that free will means "randomly do[ing] random stuff." Instead, he sees free will as the "interface between the certain and the uncertain" - the ability to make decisions and imagine things within the constraints of the physical world. As he puts it, "It's not as Yashar was saying to me, 'Randomness goes and you just randomly do random stuff.' It is that you are set free a little on your trajectory."

Cronin also suggests that selection, or the persistence of objects that could otherwise decay, is a fundamental "creative force" in the universe that generates novelty and allows for free will. As he states, "I think selection is the force in the universe. It creates novelty."

lexfridman.com/lee-cronin-3-transcript

evolutionnews.org/2023/02/on-the-origin-of-life-james-tour-exposes-the-irrelevance-of-lee-cronins-research

youtube.com/watch?v=ZecQ64l-gKM

rogerebert.com/reviews/evil-dead-rise-movie-review-2023

Joscha Bach

- v1: Free will is a representation that a decision was made based on the best understanding. It's an outflow of a control algorithm. The opposite of free will is compulsion and randomness, not determinism or coercion.

- v2: Free will is an intermediate representation, what decision-making under uncertainty looks like from your own perspective before deconstructing the process.

- We experience things because neurons implement a model/simulation of what it's like to be a person making choices in a complex world. We find ourselves in that "dream" woven by the brain.

Joscha Bach believes that the sense of self and free will is an illusion created by the brain to help it navigate the world. He argues that our perception of reality is a narrative constructed by the brain, and that our "self" is not a real entity but rather a model the brain uses to predict and control the body.

Specifically, Bach states that "our sense of self is an illusion fostered by the brain because it's helpful for it to have a model of what a person (ie, the body in which the brain is hosted) will do. Since this model of the self in fact has some control over the body (but not complete control!), we tend to believe the illusion that the self indeed exists. This is nevertheless not true."

In other words, Bach sees free will as an illusion, as our actions are ultimately determined by unconscious processes in the brain, rather than a separate "self" making decisions. However, he acknowledges that this model of the self still has some control over the body, even if it is not a fully autonomous entity.

organism.earth/library/document/lfp392-joscha-bach

happyscribe.com/public/lex-fridman-podcast-artificial-intelligence-ai/101-joscha-bach-artificial-consciousness-and-the-nature-of-reality

rupertspira.com/non-duality/blog/talks/we-cant-pull-the-world-out-of-a-description-of-the-world

news.ycombinator.com/item?id=36098332

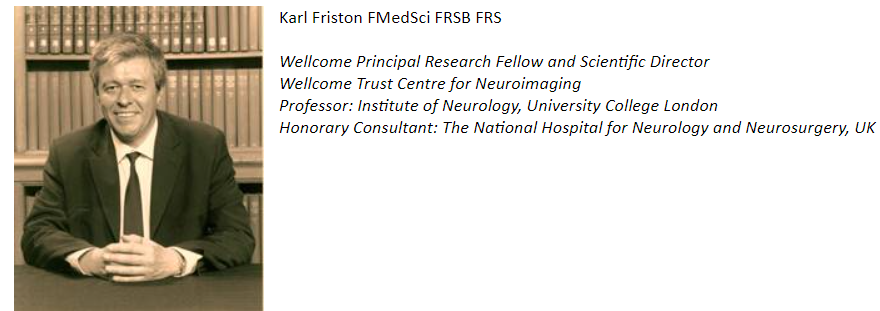

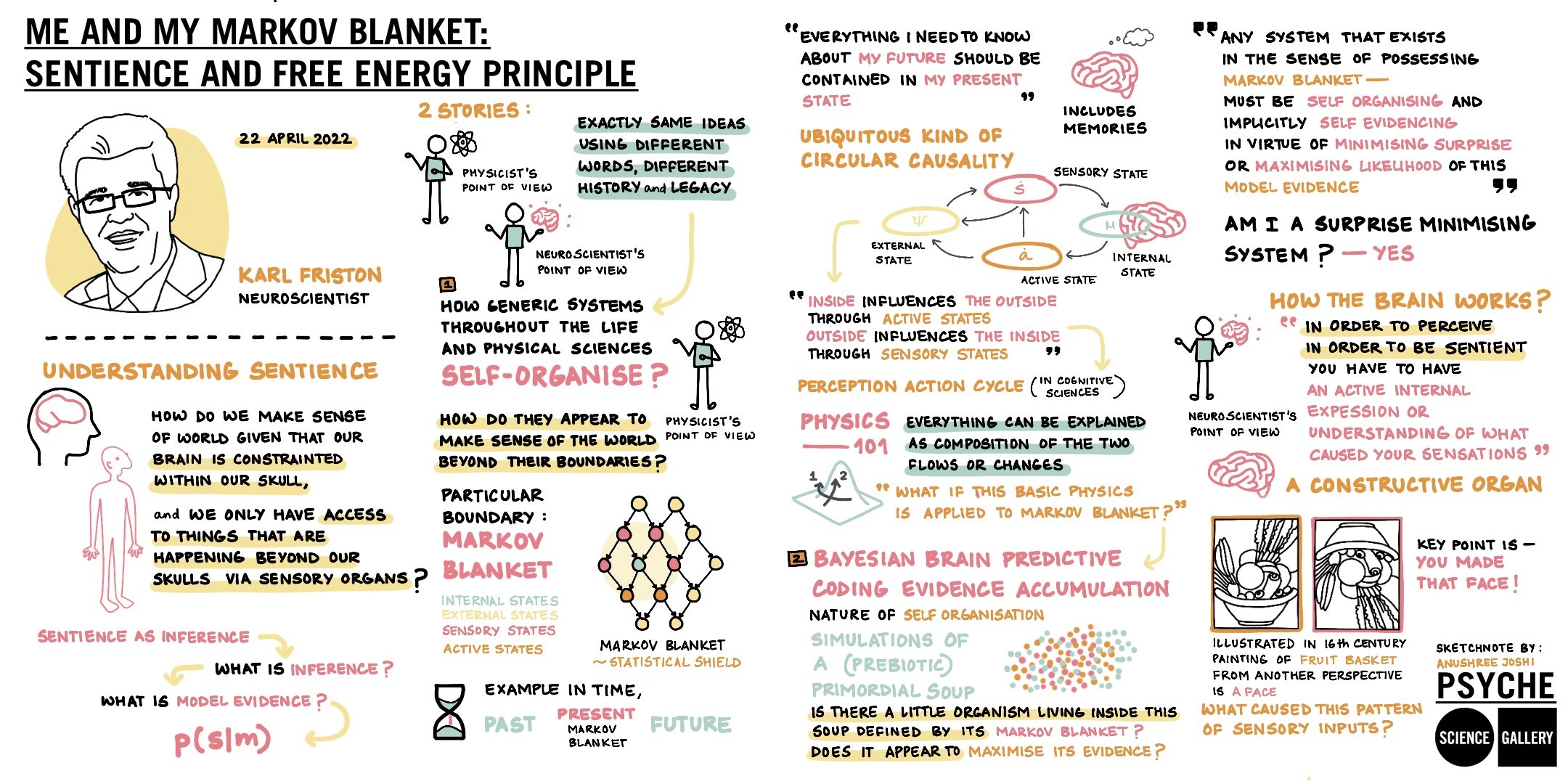

Karl Friston

- There is mathematical/computational space for free will in how biological systems/agents minimize surprise by both changing their models and by taking actions to make sensations match predictions (a self-fulfilling prophecy).

Friston's key idea is that living systems, from plants to humans, act in ways that tend to minimize "free energy" or "surprise". This is the core of his "free energy principle" (FEP).

Friston explains that agents (like humans) need to maintain their states within a limited set of "viable" states, and they do this by minimizing the "free energy" or "surprise" associated with their sensations. This allows them to avoid states that would be surprising or improbable given their model of the world.

In Friston's view, this free energy minimization is the fundamental imperative that governs the behavior of all living systems, and it can be seen as the basis for their "cognitive" or "agentic" capacities, even in organisms without a nervous system.

Friston suggests that this free energy minimization principle can provide a "mark of the cognitive" that avoids the pitfalls of either underestimating or over intellectualizing the minds of non-human organisms. On this view, cognition is not limited to human-like reasoning, but is a more general property of any system that acts to minimize free energy.

slatestarcodex.com/2018/03/04/god-help-us-lets-try-to-understand-friston-on-free-energy

jaredtumiel.github.io/blog/2020/08/08/free-energy1.html

link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10539-021-09788-0

frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00130/full

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3347222

Noam Chomsky

- We all intuitively believe we can make decisions, even brilliant people who argue against free will still behave otherwise.

- Experiments show a delay between decisions and awareness of them, but this just pushes the question of free will back a step, it doesn't negate it.

- Science tells us we can't incorporate free will into our current understanding, not that it definitely doesn't exist. Quantum indeterminacy arguments aren't convincing.

- Even people who argue free will is an illusion don't behave any differently than those who believe in it. It doesn't seem possible to live/function as if there is no free will.

- Questions of unconscious neural activity preceding conscious decisions don't negate free will, they just raise the question of what determines the unconscious neural activity itself.

"If you believe that there is no freedom of the will, why bother presenting an argument?" Chomsky suggests that the question of free will is a deep philosophical puzzle that we may not be able to fully understand due to the limitations of our own cognitive abilities. He states: "My hunch — and it's no more than a guess — is that the answer to the riddle of free will lies in the fact that there are true scientific theories that our genetically determined brain structures will prevent us from being able to fully comprehend."

Chomsky argues that just as there may be certain types of mazes that a rat is not biologically capable of solving, there may be fundamental truths about free will that are beyond the grasp of the human mind. He says: "In my opinion, all of [our human abilities] do [fall into the same mysterious category as free will]." Chomsky believes that the limits of our understanding extend not just to free will, but to many aspects of the human experience, including our aesthetic sensibilities and scientific knowledge.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZYiv790TfzI

libcom.org/article/value-noam-chomsky

iep.utm.edu/chomsky-philosophy

chomsky.info/198311__

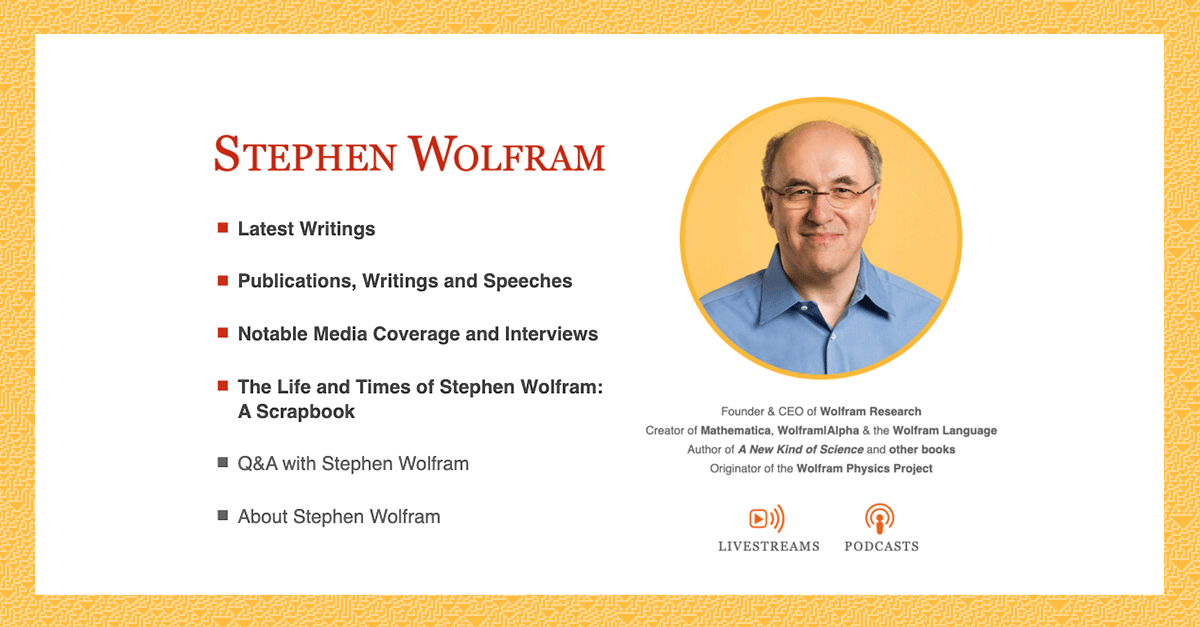

Stephen Wolfram

- The notion of "computational irreducibility" in his physics models - that some complex systemic behaviors can't be predicted without actually running through each step - may connect to ideas of free will.

Wolfram believes that the apparent free will and unpredictability we observe in human behavior can be explained by the concept of "computational irreducibility". This means that even if the underlying processes in the brain are deterministic, the resulting behavior can be so complex that it becomes practically impossible to predict or reduce to simple rules.

Wolfram argues that the traditional view that deterministic processes must lead to predictable behavior is mistaken. He says that "simple deterministic underpinnings can result in very complex and seemingly random behavior". The unpredictability arising from computational irreducibility is what gives rise to the "appearance of free will", even if the brain's operations are ultimately deterministic.

Wolfram does not believe that quantum indeterminacy or external supernatural influences are necessary to explain free will. He thinks the complexity and unpredictability inherent in deterministic systems is sufficient to account for the phenomenon of free will as we experience it.

However, Wolfram acknowledges that his view on free will is speculative and may not fully resolve the long-standing philosophical debates on the topic. He suggests that science, rather than philosophy, may ultimately provide the answers to questions about free will.

In summary, Wolfram proposes that computational irreducibility in deterministic systems is the key to understanding the apparent free will we observe in human behavior, without needing to invoke quantum effects or supernatural explanations.

johnhorgan.org/cross-check/quantum-mechanics-free-will-and-the-game-of-life

turingchurch.net/computational-irreducibility-in-wolframs-digital-physics-and-free-will-e413e496eb0a?gi=d9d6a043b3fd

whyevolutionistrue.com/2012/07/07/stephen-wolfram-and-i-on-free-will

www.wolframscience.com/nks/p752--the-phenomenon-of-free-will

Jonathan Blow

- Typical framings of the free will question assume an overly simplistic picture of reality. With a sufficiently sophisticated understanding, the question dissolves or stops making sense.

- Under interpretations like Everettian quantum mechanics where all possibilities occur, or questions of subjective experience across replays, it becomes unclear how to even define free will coherently.

Thomas Campbell

- In his theory, the "free will awareness unit" we identify with is a temporary partitioned data stream from a larger individuated consciousness. It doesn't continue after death, only the accumulated learning does.

- Expecting specific relationships to continue after death is dysfunctional. Each life is a new experience, like moving to a new grade with a new teacher and classmates.

John Vervaeke

- Identifies as a compatibilist - free will is the cognitive state being most causally relevant to behavior, not behavior being uncaused.

- Doesn't see a coherent reason to posit or value some "uncaused cause" notion of free will that is independent of reasons/reasoning. Still seems incoherent.

John Vervaeke, a philosopher and cognitive scientist, has discussed the topic of free will in his work. Vervaeke sees a deep connection between our cognitive structures and the structures of reality. He argues that reality is not purely deterministic, but rather has both orderly, predictable aspects as well as chaotic, unpredictable elements.

Vervaeke agrees with physicist Lee Smolin that the demand for certainty in our predictions is premised on a deterministic view of reality that has been undermined by modern science. Instead, Vervaeke suggests that reality mirrors the fundamental features of human cognition, which includes both algorithmic, rule-following processes as well as arbitrary, unpredictable aspects.

This perspective implies that free will is not an illusion, but rather reflects the open, unpredictable nature of reality itself. Vervaeke sees this as a more promising approach than traditional virtue ethics or modern ethical theories. His views on free will and the relationship between cognition and reality are further explored in discussions with other philosophers like Michael Levin.

John Vervaeke & Joscha Bach

- Vervaeke is a compatibilist - free will is our cognitive state being the most causally relevant explanation for our responsible/responsive behaviors, not some uncaused cause.

- Bach sees free will as an appearance arising from the self-modeling of intelligent systems before that self-model gets deconstructed.

philosophy.stackexchange.com/questions/82325/wisdom-and-john-vervaekes-awakening-from-the-meaning-crises

iai.tv/articles/the-future-is-radically-open-auid-2182

www.meaningcrisis.co

www.youtube.com/watch?v=nWMSlcZbEMw&t=1

James Robert Brown

- Intuitively believes in and lives as if he has free will, doesn't know how to operate otherwise. Understands arguments against it but isn't fully convinced.

- Under emergentist (not reductionist) worldviews, free will could potentially emerge at higher levels of complexity, not from fundamental physics.

Anil Seth

- Sees free will as another kind of perceptual experience, the feeling of being free. The debate over determinism is irrelevant to the actual experience and functioning of volition.

Anil Seth does not believe in a "spooky" or libertarian form of free will where our conscious self causally intervenes in the flow of events.

However, Seth argues that the conscious experience of volition, or the feeling that we are making choices, is real and important for our survival and behavior.

Seth sees the experience of free will as a kind of perception or hallucination, similar to our visual experiences, rather than a direct reflection of an underlying reality where we have the ability to choose between alternative possibilities.

He suggests the reason we have this experience of volition is that it is useful for predicting and controlling our actions, even if it does not correspond to an actual causal power of the conscious self.

In this view, free will is an illusion, but an important and real part of our conscious experience that should not be dismissed. Seth is a compatibilist who believes we can maintain notions of moral responsibility even without libertarian free will.

mountainsrivers.com/2022/12/19/consciousness-and-free-will-part-1

iai.tv/articles/anil-seth-the-hallucination-of-consciousness-auid-2525

www.newscientist.com/article/dn22144-brain-might-not-stand-in-the-way-of-free-will

www.youtube.com/watch?v=478WUta-Cys

selfawarepatterns.com/2021/11/20/anil-seths-theory-of-consciousness

Primary Referenced Sources:

This section is based on the insights and arguments presented in the event "World's Largest FREE WILL Debate with Top Physicists & Philosophers," hosted by Theories of Everything with Curt Jaimungal, accessible here.

- Curt Jaimungal's 'Theories of Everything' YouTube Channel - "World's Largest FREE WILL Debate w/ Top Physicists & Philosophers". Watch here.

- Michael Levin on self-perception and identity, available here.

- David Wolpert - Overview of free will concepts. Details on Wikipedia.

- Donald Hoffman discusses the evolutionary arguments against reality, detailed in this Quanta Magazine article.

- Stuart Hameroff on quantum consciousness, explained in-depth here.

- Wolfgang Smith explores the intersection of science and myth in his essay available here.

- Bernardo Kastrup on the mechanics of free will, presented here.

- Scott Aaronson probes into philosophical and computational aspects of free will on his blog.

- Joscha Bach discusses foundational principles of cognition in this document here.

- Karl Friston on the free energy principle in neuroscience, detailed here

- Noam Chomsky discusses human nature and free will in this interview.

- Stephen Wolfram examines quantum mechanics and free will, available in this interview here.

- John Vervaeke on the radical openness of the future, discussed here.

- Anil Seth explores the concept of consciousness as a hallucination in this article here